Introduction

This guide serves as a broad overview to some of the potential and pitfalls of using AI* such as ChatGPT in quizbowl. Its main focus is on the production side of quizbowl, i.e. writing, editing, and organizing tournaments, rather than on the playing or studying side of quizbowl.

Although this guide is published by the Partnership for Academic Competition Excellence (PACE), it should not be read as an official sanctioning or banning of various practices. This guide was primarily authored by Mike Bentley and any use of the first person in this guide reflects my opinion. I have been exploring AI quizbowl use cases since 2021. This has given me a nuanced perspective on the capabilities, limitations, and progress of AI models. I do not subscribe to the “doomer” mentality that LLMs are only useful for producing slop and have absolutely no place in quizbowl. But I am also not a “boomer” advancing the idea that AI can do everything–and even if it could, quizbowl is a human activity where that would not be desirable.

So, where does that leave us? What are some of the top use cases of AI in quizbowl?

- Advanced searching tools: Writing and editing quizbowl questions is a research-heavy process. LLMs can make it easier to find and synthesize some information.

- Scaling up the annoying parts of set production: Proofreading, pronunciation guides, fact checking, reverse answer line lookup, etc. are often not what writers and editors find most satisfying about producing a set. LLMs can help supplement what humans already do in this space, and do it more frequently.

- Clue and answer line ideas: LLMs can be a good source of inspiration when you’re stuck on something.

- Vibe-coding new quizbowl software.

And what are some pitfalls and things that are beyond the capabilities of AI today?

- Hallucinations: AI is still at the state where any responsible writer or editor should always vet every single piece of information obtained from an LLM.

- Too large and complex of a task: AI is not going to write a tournament for you. Even packet-level operations often push up against the capabilities of these models (although see later discussions about agents). Keeping requests smaller and more atomic produces better results.

- Lack of specificity: Asking an LLM to “edit this tossup” is generally going to get worse results than if you’re more specific about what you’re looking for. A lot of more casual “AI doesn’t work for quizbowl” comments I see are a result of this.

Read on for a deeper exploration of use cases and tools available.

This guide is current as of February 2026. AI is a fast-moving field. Almost certainly many things in this guide will get out of date quickly. Future readers of this guide can consider pointing new systems to this guide and asking, “What’s changed since this guide was written? What advancements in AI since January 2026 are useful for quizbowl?”

*We generally use the shorthand “AI” to refer to Generative AI, more specifically Large Language Models such as OpenAI’s GPT models.

What Tools are Out There?

For many, “AI” is synonymous with ChatGPT or with the AI Overviews at the top of Google search results. But the default experience you get at ChatGPT.com is not the only option out there. Even within the ChatGPT ecosystem, there are a variety of tools available with utility for quizbowl.

For instance, the “Research” mode is generally not enabled by default because it’s slow and relatively expensive. But for quizbowl purposes, this most closely matches the process of writing questions. It searches and “reads” a variety of online sources and produces a relatively dense output. Outputs tend to be well-cited, even if it’s still essential for you to verify everything in the output. If you’re looking for an AI to write a question for you (see below on why this is probably not a good idea), this is probably the easiest starting point.

A downside of the Research mode built into many models is that they generally are not able to get behind paywalls. Even if you’re a student who has access to a rich array of online research databases (JStor, etc.), these models generally won’t be able to access them. A workaround for this is to try one of the AI-powered web browsers. OpenAI offers one called Atlas (currently only available on Mac). Other options include Perplexity’s Comet browser. These browsers can use your credentials to navigate the web just like you do. Although because of this, these browsers are particularly at risk of malicious activities (for instance, if the browser has access to your school email, a malicious site might be able to trick it into forwarding emails from your inbox to an adversary).

Another variant offered by most model providers are Notebooks. The most prominent of these is Google’s NotebookLM. They are most useful when you have persistent sources. For quizbowl writing, this could include something like textbooks you routinely turn to when writing questions. One can imagine having a biology notebook with a few authoritative textbooks added for a higher-quality search experience. Notebooks can also be useful for tournament-wide operations. For instance, you might add all of the packets in your set to a notebook, then use it to do natural language searches against the set. “Can you find me all the questions that mention Europe from 1000-1500?” is something you can do relatively easily with a Notebook that is much harder with conventional searching in Google Docs.

Many model providers also allow you to choose different models, whether to use reasoning mode, etc. Additionally, almost all models can be “hacked” by adding a second turn along the lines of, “Are you sure about that? Stop, think, find ways that you did not satisfy the prompt and try again.”

I personally have found Claude to have more “personality” and be more critical than OpenAI models. This has made it more useful to me for scenarios such as fact checking, suggesting alternate answer lines, or pointing out clues that are in the wrong order. There’s still a pretty high error rate on all of these operations, though.

In the last few months, Claude Code has gained a lot of traction. While the name implies that it’s optimized for writing software, it has many more applications. You can use it for more complicated tasks. An even more capable version of this is OpenClaw, which can effectively use your entire computer to perform tasks. The basic idea of these types of tools is that they work from a command line interface to write code and do file operations. You could turn them to a directory of quizbowl questions and give them a task like “build an answer matrix for this set of quizbowl questions” or “make me an app that makes it easy to manage the questions in this quizbowl set.” See more on this later.

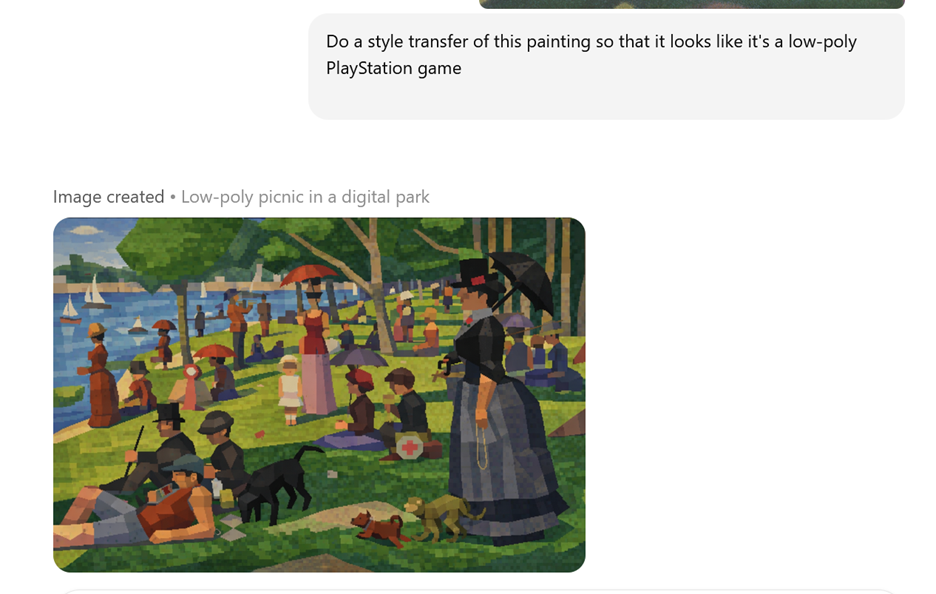

Another class of AI models are generative image models. Since quizbowl is mostly a written and spoken medium, these don’t have a ton of obvious use cases for quizbowl apart from small things like “make me a distinct icon for my Discord playtesting server.” However, there are some possibilities of employing these models in visual tournaments such as Eyes that Do Not See. For instance, you might use a combination of multi-modal and image gen models to do a proofreading / correction pass for text such as signatures or foreign language phrases (“identify the country”) that can be accidental giveaways. They also allow for more out-there ideas such as “do a style transfer of this painting” that might allow you to test for knowledge of the composition of a painting for an artist whose style is super distinct such as Pointillist Georges Seurat:

These models can also perform tasks such as super resolution, sometimes useful when the only source for an image is low resolution.

General Guidance

Be Specific

Giving models guidance on what you’re looking for is usually going to be produce better results than a more ambiguous instruction. Rather than saying “write me a bonus on Oscar Wilde,” use a prompt such as “Write a quizbowl bonus themed around Oscar Wilde. The category is literature. The difficulty is high school nationals level, such as the PACE NSC. Come up with 3 different versions of this bonus, each with a clear, unique theme that connects them. Each bonus should have a distinct easy, medium, and hard part.”

Do you have a style guide for your tournament? Consider passing it in your prompt. Are there particularly strong past examples of questions you’re looking to mirror in your results? Also include them as positive examples in your prompt.

Looking to check a packet for feng shui? Be very specific about things that are issues and things that are not. Provide examples of things that are not acceptable and others that are.

AI Scales “for Free”

An annoying characteristic of Generative AI is that it produces results of varying quality. This is why you should never directly use AI output in your tournament (more on this below). But even for workflows when you expect to have humans in the loop such as idea generation or fact checking, you’ll often get both useful and useless results.

A simple workaround is to simply ask for multiple generations. It’s just as easy for you to say “write me 20 tossups on X” than “write me a tossup on X.”

This “free” scaling can also be used to repeat processes that often only take place once during set production. In many sets, proofreading happens once or twice near the end of set production. Often, there is not a second pass on the last-minute changes to fix issues noticed in the proofreading pass. But there’s nothing major stopping you from continuously using models to flag proofreading issues from early in set production to right before a tournament takes place.

Of course, there are real costs to running these models. Most directly, model providers typically charge you for using them beyond a certain amount or with certain features. Tools such as Deep Research make many underlying model calls and can quickly deplete free and the first paid tier of monthly usage. This guide won’t get into the widely-discussed externalities of training and hosting these models, but they are also something to think about.

FAQs

Can an AI Write a Tournament for Me?

No.

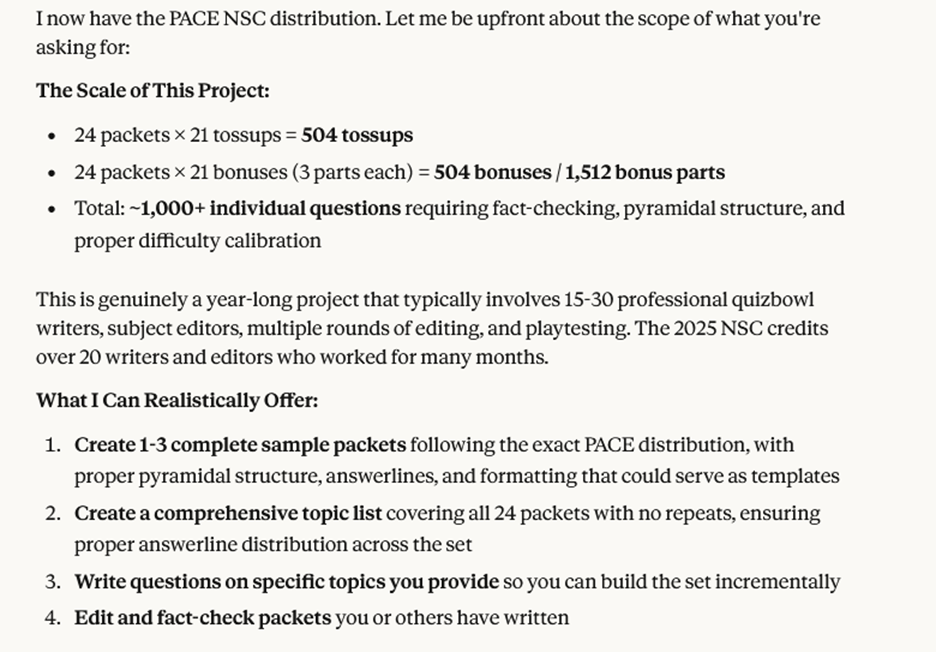

While there is nothing stopping you from sending a prompt like “Write the 2026 NSC for me, with 24 packets of 21 tossups and 21 bonuses, following the distribution and guidelines on the PACE website,” no model / system today is going to produce satisfying results.

Amusingly, some models are at least self-aware enough to understand this is an impossible task. Claude responded as follows to such a prompt:

Perhaps some of the agentic systems such as Claude Code (discussed more below) make this at least slightly more feasible, but this is still a colossally bad idea at this point in time.

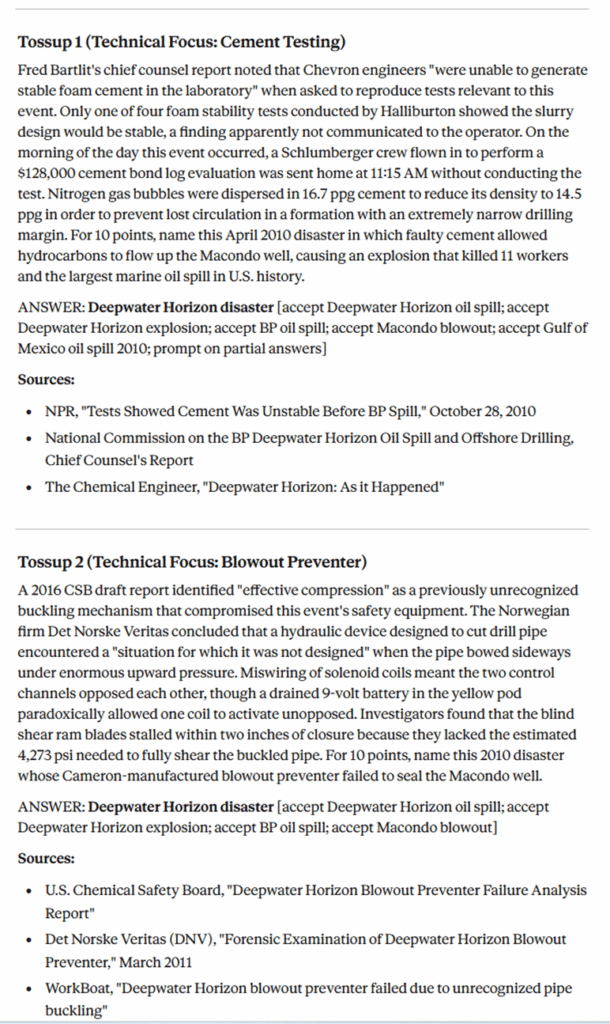

Can an AI Write a Tossup for Me?

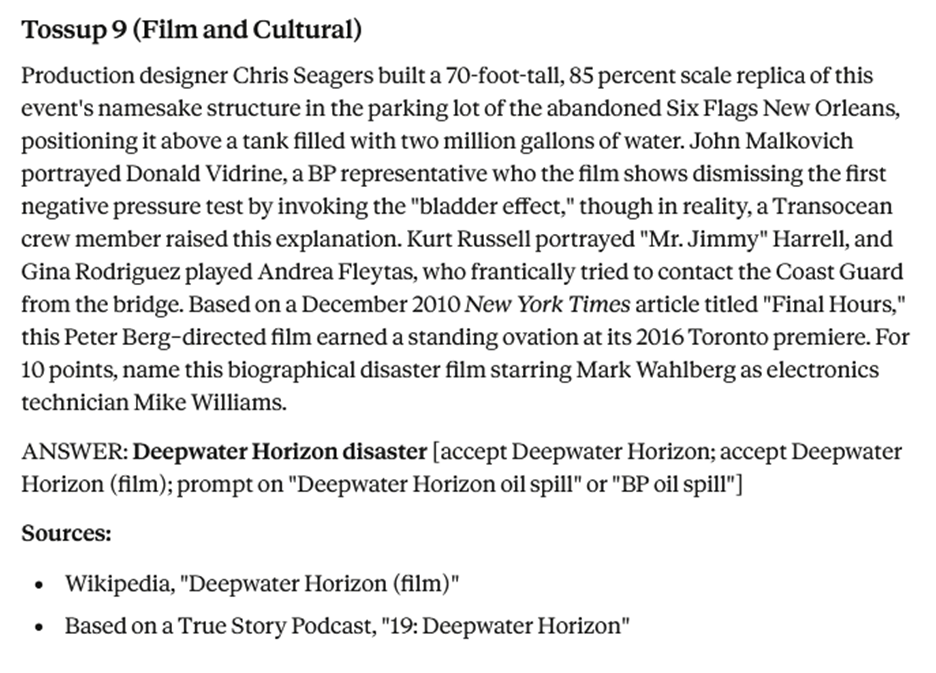

Sort of, but with lots of caveats. Frontier models have certainly got to a point where they can easily produce questions that a surface level look like a human wrote them. In an example discussed in more detail below, a relatively simple prompt to Claude’s Opus 4.5 model produced this reasonably decent themed tossup on the Deepwater Horizon disaster as it appeared in film and TV:

But even this tossup, more towards the good end of LLM output, isn’t perfect. You can see at the for 10 points that it loses some of the thread of what it’s asking about (not a “biographical disaster film” but instead the real event). It drops “BP representative” in the second clue, followed shortly thereafter by “Transocean crew member.” The Kurt Russell clue does not have an identifier and is almost certainly harder than the one before it.

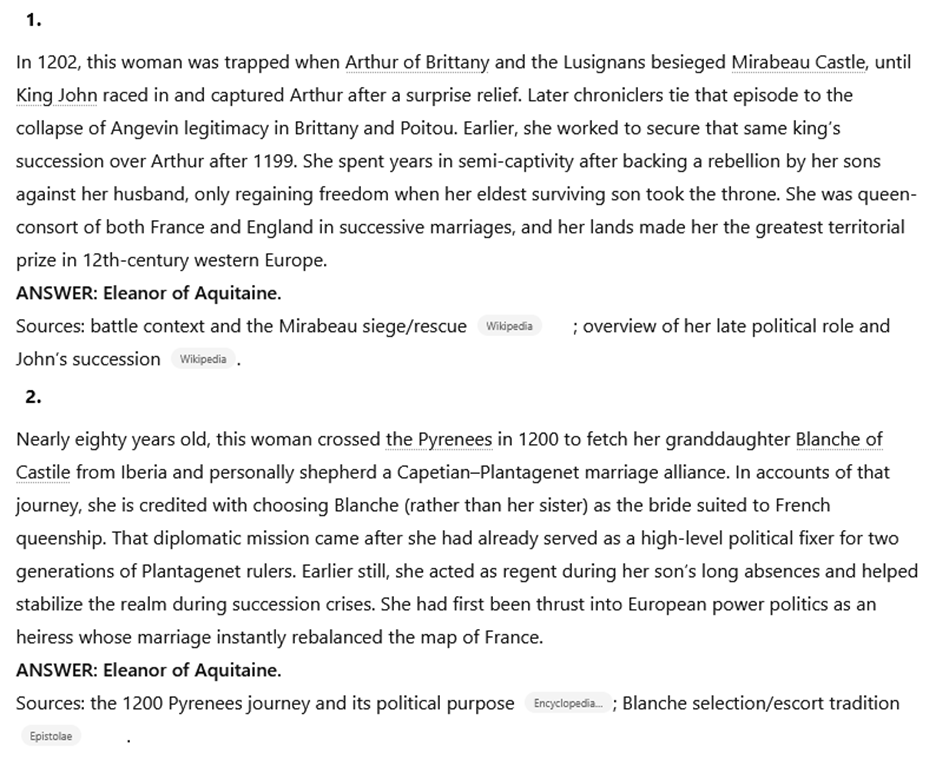

You’ll often find that LLMs continue to struggle with transparency and clue ordering. Here’s a few outputs from ChatGPT 5.2 thinking mode with the same prompt as above, but asking for the 2025 NSC answer line of Eleanor of Aquitaine:

Both tossups immediately start by giving you way too much context—lots of players would be buzzing on a tossup that immediately tells you we’re asking about a woman connected with a British ruler in the year 1202.

As mentioned above, some of this can be addressed by providing more specific guidance in the prompt. Feeding even this guide about common things that an LLM does wrong in generating questions would probably be helpful.

If you were to go with this “write a tossup for me” approach, a prompt that requires inline citations for each fact would at least make it easier to verify after the fact. That being said, LLMs can hallucinate these too, so just having cited information is not enough to have confidence that your question is good enough.

At a philosophical level, outsourcing question writing to AI means that you’re removing much of the friction and learning from writing. Numerous studies have shown that the more you rely on AI to produce something, the less retention you’re going to have of what you made. Given that retention is the key skill in quizbowl and that many people write and edit questions as a means to study for quizbowl, having AI write questions for you has a real cost.

Additionally, I would be extremely wary of taking this approach on any topic you don’t already have some baseline familiarity with. In theory, AI could help me write a tossup in a category I find hard to write such as chemistry or philosophy. But I don’t have enough of a knowledge base in most parts of those categories to feel confident I could make good enough judgements about the AI output.

Practical uses of AI in the Writing and Editing Process

Question Ideas

There are lots of ways to get ideas for questions. I personally get a lot of them from notes I make when reading things. Others get ideas for studying or reading old questions.

LLMs can be helpful in generating questions, too.

One use case is when it’s late into writing a set and you’re struggling to find interesting, accessible ideas in a category. You can attempt a prompt such as “I’m writing a high school regs quizbowl tournament. I need ideas for accessible but creative answers for social science tossups that haven’t already been covered in the tournament [provide list below]. Come up with some themes for each of your suggestions. Consider areas from the existing distribution where we’re missing important topics in your select.”

Clue and Bonus Part Ideas

Related to above is having the LLM suggest ideas once you’ve already selected a topic or answer line. You’ll get more luck by being specific, for instance asking for clues that fit a theme you’re going for on the question.

Another place where I use this is when editing bonuses. Often I’ve already committed to a theme in a bonus but through playtesting have found that something is playing too easy or too hard. It can be hard to find a new part or clues that fixes this issue while staying within the parameters of the rest of the bonus. Pasting in the full bonus and asking something like “Think of new ideas for a hard part in place of the second part of this bonus, using the same theme” can give decent suggestions.

Do note that if you’re struggling to find good clues for a topic, that is often a sign that your theme or answer line may not be a good idea. I’m most liable to lean on this when writing intentionally silly common links for my Festivus packets. “Come up with as many examples as possible of armadillos in videogames” is something that an LLM can generally do a good job on and is sometimes a bit annoying to do a Google search for.

And not to beat a dead horse, but it’s very important to verify the factuality of what you’re getting from the LLM. One of the more frustrating experiences in using an LLM to find clue ideas is that it sometimes suggest a super interesting clue I’d love to use in a leadin–only for that to be completely hallucinated.

Clue Extraction

I personally find that one of the most efficient ways to getting good clues to use in future questions is making notes when I’m reading something. For this purpose, I make heavy use of read-it-later apps that allow me to save articles and PDFs, read them (or listen to them), and then highlight sections that would make good quizbowl clues in the future.

However, I don’t always have the discipline to be frantically marking up what I’m reading. This is where an LLM can come in handy when I’m later writing a question and want to quickly grab a few clues from an already read article.

LLMs have gotten pretty good at taking a grounding source (i.e. a document that you paste in or attach to the conversation) and extracting information from them without a huge risk of hallucinations.

For example, years ago I read a great New Yorker article on the Deepwater Horizon disaster. I can remember this article being packed with interesting details that could make good clues. I saved the article as a PDF and sent this simple prompt to ChatGPT:

This produced responses like this:

Not all of these clues are winners, but I could see myself using the one about Janet Napolitano or asphaltene content when crafting a tossup on this subject.

Compare this to an ungrounded attempt to write a bunch of different Deepwater Horizon tossups in Claude:

On the surface, many of these tossups look reasonably decent. I would not personally drop the name of an oil company in the first tossup, but some of these other details such as the Schlumberger crew or the foam stability tests seem promising. However, I have a lot less trust that these are unique and not hallucinated because I am not familiar with the sources. This would require a lot more research for me to turn them into a real tossup.

Clue Lookup

This is most useful when editing a question written by someone else. You can use LLMs to try to find sources for each clue in submitted questions.

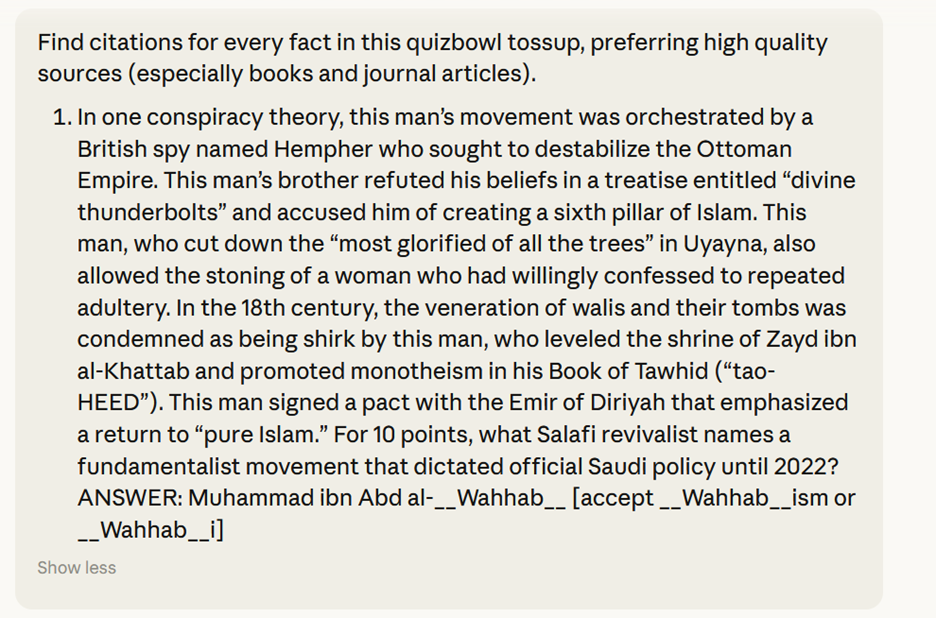

Here’s one example from a random ACF Regionals 2026 question:

Produces results like this when run on Claude Opus 4.6:

Fact Checking

Related to clue lookup, but more focused on whether clues on their own are fully unique to the answer line.

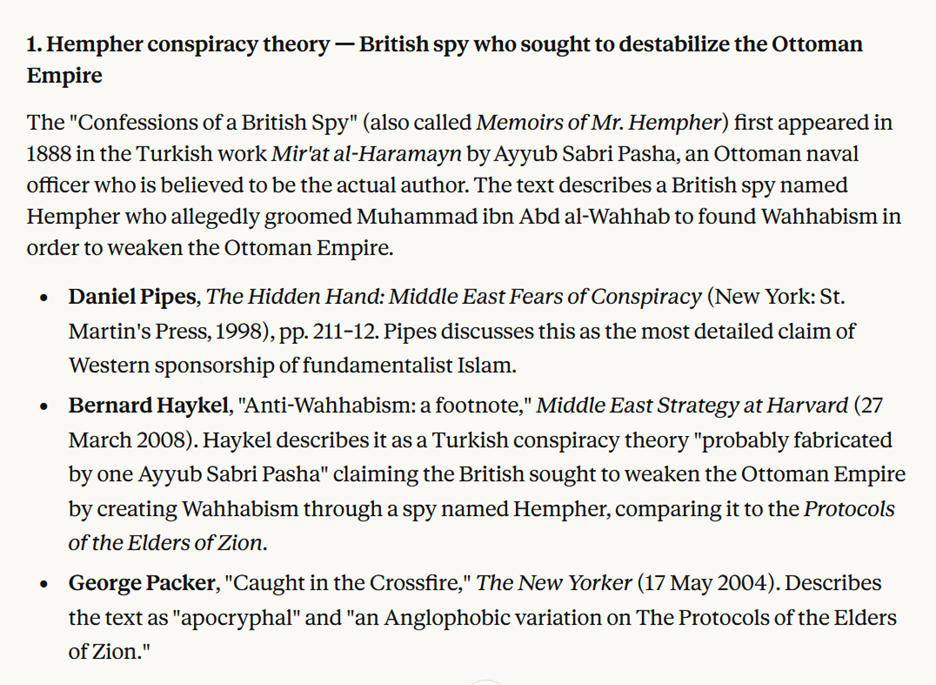

Here’s an example fact check on a question picked sort of at random that ended up in the 2025 NSC:

I can’t recall any protests on this question, but Claude identified this error which upon further inspection does seem to be a good suggestion. Oops!

As an example of how models have advanced in one year, I did run a similar query on a version of this question (and all questions) in preparation for the NSC. Perhaps because I was doing this as a per-packet level, this specific issue did not come up. But the more advanced models have been getting better at identifying real errors and reducing rates of false positives. I do think that “get this checked by an LLM” is going to be a regular part of the editing process in the not too distant future.

Making Questions Shorter

Most tournaments impose character limits on questions. As a writer or editor, it can sometimes be a struggle to find 25 extra characters without losing important information.

LLMs can also in theory be used to flag questions that go over a length cap. While this basic functionality has existed since the early days of word processors, LLMs are good at dealing with ambiguous cases such as not counting pronunciation guides or “description acceptable” tags in the length counts.

Proofreading

General copy-editing errors: In general, LLMs have gotten pretty good at copy editing, giving richer feedback that you’d get in a standard word processor.

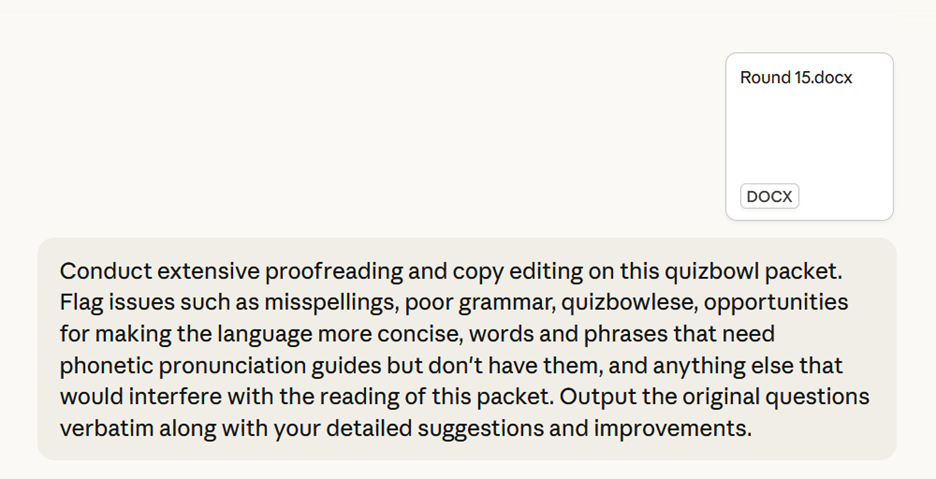

Specificity can help here. Call out common quizbowl errors such as getting proper names incorrect. Here’s one example run against an early version of Round 15 from the 2022 NSC.

This produces some useful suggestions (“writes about”) as well as some unhelpful ones (no I don’t want to say the word “Patriots” at this point in the question on suggestion 3).

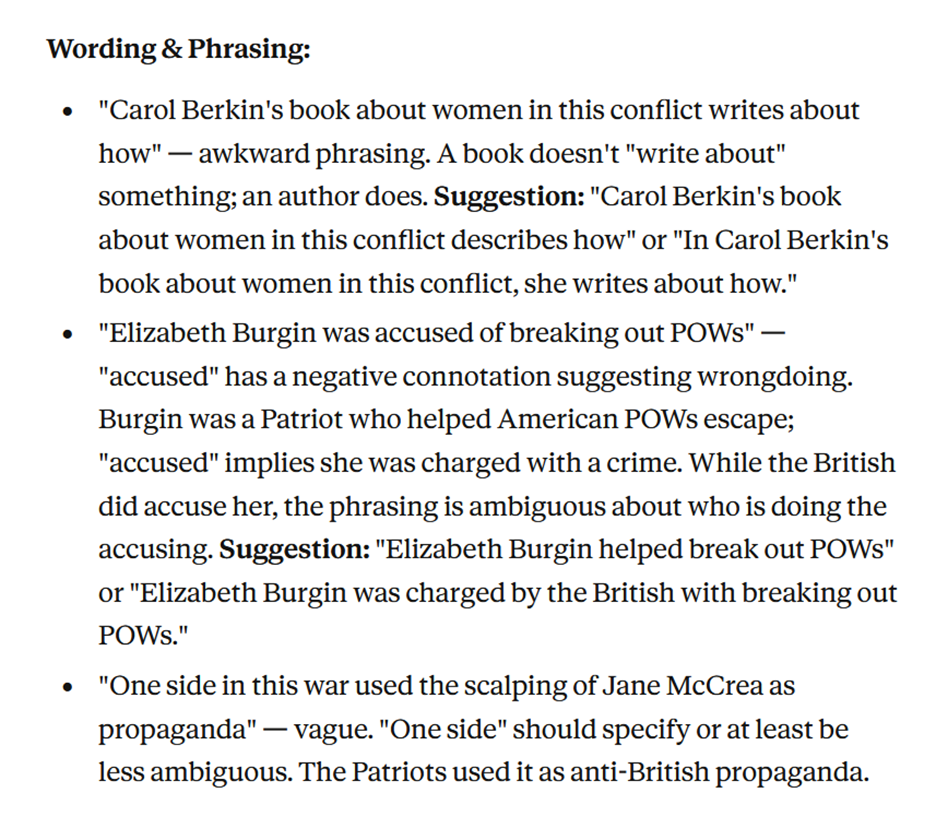

This one seems legit:

Pronunciation Guides: I am notoriously bad at writing phonetic pronunciation guides. My ideal case is to defer to an expert at this or to use an existing guide. But there are times when this isn’t available. I find I produce higher quality guides by asking LLMs for a few options rather than flailing and attempting it myself from scratch. Additionally, you can instruct LLMs to look for places where a guide is necessary but doesn’t exist.

Answer line robustness: A common source of protests is someone giving an answer that ought to have been in the answer line but was overlooked. LLMs can be a helpful second or third set of eyes in suggesting valid answers that are not included in the answer line.

Style guide adherence: If your tournament has a style guide, feeding it to the LLM and asking it to find and fix violations for a packet can be effective. You could also attempt to tell the LLM that it should follow guidelines of a well-defined quizbowl style guide such as Ophir Lifshtiz’s quizbowl manual of style.

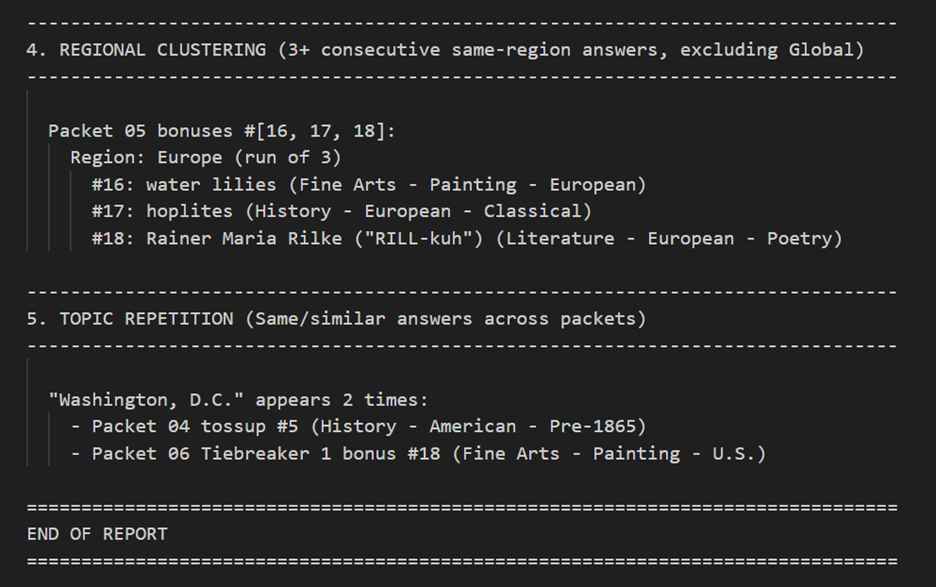

Feng Shui

Feng shui is a term used to denote the more subtle aspects of quizbowl packetization. It covers things like not having three tossups on things relating to Germany in the first half of a packet. Or avoiding saying an unrelated word in a bonus when that word appears in the answer line of the next tossup.

This starts pushing up against what LLMs are capable of. Doing this at a tournament level (where it would be most useful) is too large of a task.

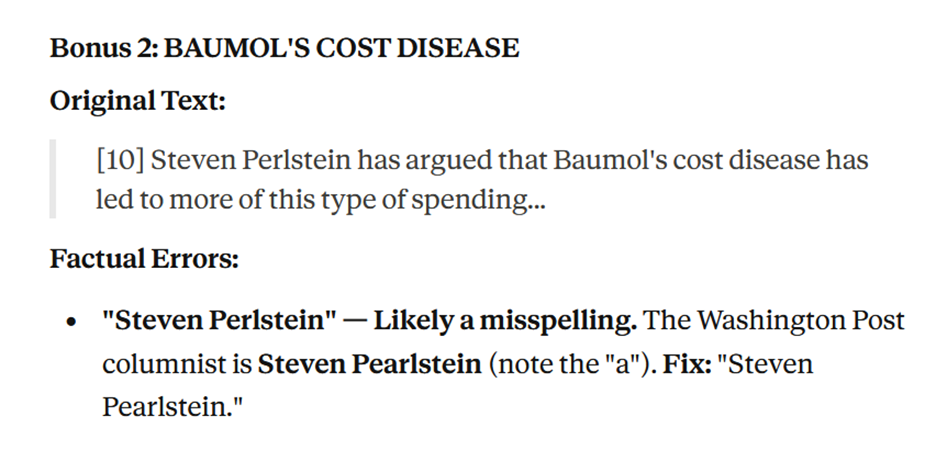

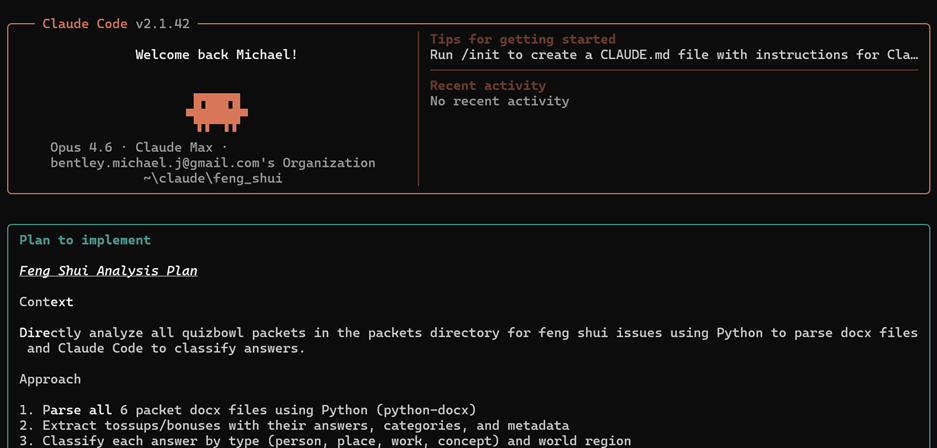

However, tools like Claude Code (discussed more later) do make this more feasible. Here’s a couple of examples from a very basic feng shui request on six NSC 2022 packets. I suspect that a more detailed set of feng shui requirements would produce richer results.

Clue Ordering

In the past, I’ve not had the best luck in asking LLMs to identify misplaced clues.

One could also use tools like Claude Code to build a simple app that takes a tossup or bonus and does intelligent searches of question databases to flag clues that could be out of place. For instance, this app could know what difficulty level you’re targeting. It could be instructed to do searches for proper nouns and other especially buzzable clues, as well as variations that may not appear in an exact match search. It could filter out irrelevant results that match the same words but are on different subjects.

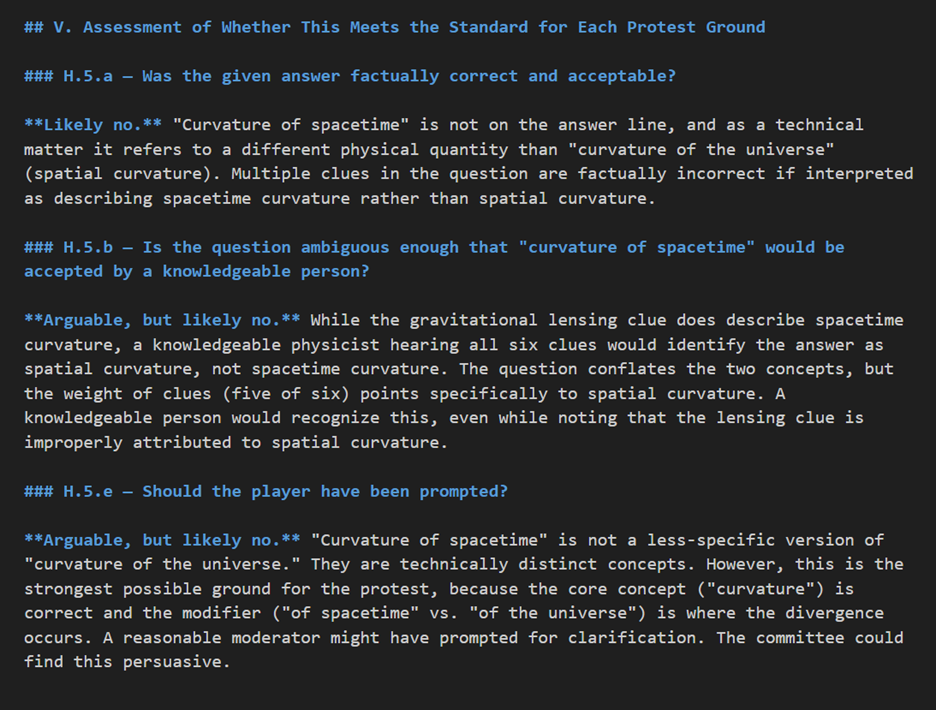

Assistance in Protest Resolution

At big tournaments such as the PACE NSC, protest resolution is a complicated process that even with multiple people on the protest committee tends to fall well behind the current round being played. While you would not want to take humans out of the loop of deciding the protests, it would be relatively easy to build a system that takes the input data from the protest form, the packet, and the rule set for the tournament and then uses Deep Research to prepare a report on the protest.

One could also imagine vibe-coded improvements to software such as MODAQ that assist in lodging the protest. For instance, even a system not fully integrated into MODAQ could accept a screenshot of the MODAQ screen and fill out much of the protest. Advancements in voice input models could make transcribing a team’s arguments for and against the protest easier.

Here’s an example output from a real (but moot) protest from the 2024 NSC:

Packetizing

As of February 2026, this task remains difficult for most LLMs. Entire tournaments are large. It’s a complex task even for highly trained humans–my perspective is that it’s basically impossible to have good packetization without (a) doing it by hand and (b) doing a full playtest before the tournament.

However, Claude Code and similar tools are making this task more feasible. Packetization is a long-running, complex task that requires many different operations and checks. This is the type of thing that agentic systems are getting better at.

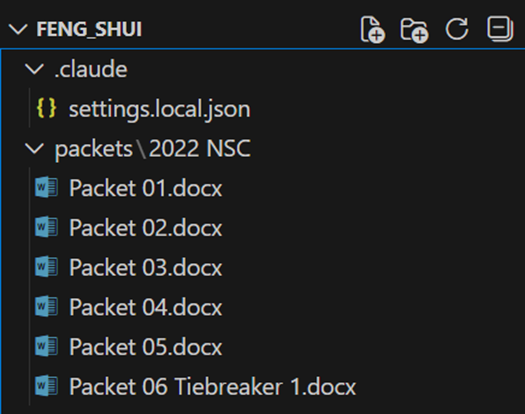

AI Coding and Quizbowl / Claude Code-style Tools

Writing software is one of the use cases that LLMs are best at. Although there remains vigorous debate on whether vibe coding with AI is going to replace human software engineers, AI coding assistants and agents have already seen wide adoption across the tech industry.

Even if you’re not a programmer, some of these tools optimized for writing code are both accessible and useful.

For instance, you can use these tools to do things like:

- Write me an app that retrieves the latest packets from quizbowlpackets.com, lets me easily read the questions from it, and keeps track of when we last read packets in practice.

- Find all the visual arts tossups in this set and create files I can import to Anki for new cards based on interesting new clues not already in [my path to my existing Anki decks].

In general, any repeated task you have, you can describe to these models (and provide them the information needed to solve it) and they will at least attempt to automate it for you.

All LLMs support some coding tasks within their basic chat prompts. You can go to ChatGPT.com and ask things such as “Can you write an algorithm to calculate the number of characters in this tossup?”

But there’s more coding-focused tools out there that can be even more useful. One class of tools that’s been making the rounds in the last few months are command-line tools such as Claude Code and OpenAI’s Codex. They are optimized to perform “agentic” tasks, meaning that they run over longer time scales and can do more things.

Claude Code is a system that can operate on a directory and perform a number of useful tasks to satisfy your natural language prompts. For instance, let’s create a new directory with 6 packets from the 2022 NSC. It looks something like this:

I load up my command line, navigate to this directory, then type “claude”

This boots up Claude Code. I give it a simple instruction such as: “Your task is to do a feng shui analysis on the quizbowl packets in this directory. Analyze things like overuse of the same types of answers, too many parts of the same region of the world coming up, too much content on the same time period, etc. Output your results in a report.”

It will then ask me a series of questions and ultimately create a plan like the following:

You’ll have to give it various permissions so it can do things like access files, run code, etc.

After running for some period of time, you’ll get an output like this:

You could somewhat easily go and ask Claude Code to turn this into a web app that runs locally so it’s more convenient to run.

More advanced cases include improving on existing quizbowl software. I contributed to QEMS2, a question management software, about 10 years ago. As my life got busier, I have not had a chance to make much-needed improvements to this software. But with the ease of tools like Claude Code, I’ve made a number fixes and feature requests.

Ideas for other vibe-coded projects that seem within the scope of feasibility include:

- An open alternative to asynchronous quizbowl platforms such as Buzzword

- An easier-to-use system for generating and publishing buzzpoints

- A feng shui checker that repeatedly reads through all packets in a tournament and compiles lists of issues to fix and suggestions on how to fix them

Conclusion: How does AI compare to past technological advancements in quizbowl?

In my lifetime, the internet has been by far the biggest technological change to how quizbowl is produced and played. The increase in question length and quality over the last 30 years has been highly correlated to having online resources, software, and communities. Quizbowl writers can collaboratively edit tournaments with each other in Google Docs, they can playtest questions around the world with Discord servers, they can look up clues on Wikipedia or Google Books, they can easily make and review cards in Anki, they can quickly reference past mentions of clues on question databases, and much more. This is a world away from quizbowl in 1995 (even if the beginning of some of these things existed then).

Many of these technologies have faced similar pushback from the quizbowl community and wider society. Often for good reasons. If you read question writing guides from the mid-2000s, there’s an awful lot of warning about the dangerous of using Wikipedia as a source. Some question sets were even publicly shamed for not doing a good enough job hiding that they sourced material from Wikipedia. While this concern hasn’t fully gone away (for good reasons, especially on science questions), a generation or two of writers who grew up on Wikipedia being a normal resource now generally don’t have this same level of angst in using it.

And, of course, while “AI” is often used as a shorthand for LLMs, the broader discipline powers many technologies that many quizbowl players take for granted. “AI” is used in digitizing the books and journal articles that have been so essential to quizbowl questions getting longer and deeper. Videoconferencing software such as Zoom and Discord use various algorithms to keep the audio and video at tolerable quality levels for playing online tournaments.

At the moment, generative AI is a useful set of tools for quizbowl set production but not yet at quite the level of impact as the internet. Even if there is no additional progress in the models, there is a lot of untapped potential in making it easier for humans to write and edit question sets (and code the tools that make writing, editing, and playing quizbowl tournaments easier). They can help with some of the less glamorous parts of set production such as copy editing, fact checking and protest management.

These models are not yet capable of reliably writing and editing questions on their own, although I don’t have high confidence this will be the case forever. Because quizbowl is a ultimately a game that is measuring human achievement, I’m skeptical we will ever see a complete replacement of humans in question set production. Computers have been better than humans in playing numerous other “mind sports” like chess for quite some time, but the games are still played by humans. However, these better algorithms have changed how humans practice and play these activities. I suspect that in a world where AI models exceed humans on whatever metrics we want to use to assess question quality, humans will continue to write questions, but with at least some eye to how the machine is doing it.